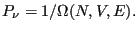

Eq. 2.1 introduced the quantity

as the number of states available to a system under the constraints of constant number of particles,

as the number of states available to a system under the constraints of constant number of particles,  , volume,

, volume,  , and energy

, and energy  . The fundamental postulate of statistical mechanics, also called the “rational basis”, is the following:

. The fundamental postulate of statistical mechanics, also called the “rational basis”, is the following:

In statistical equilibrium, all states consistent with the constraints

of  ,

,  , and

, and  are equally probable.

are equally probable.

or

|

(13) |

This relation is often referred to as a statement of the “equal a priori probabilities in state space.” Another way of saying the same thing: The probability distribution for states in the microcanonical ensemble is uniform.

This postulate reflects the fact that we are maximally uncertain with regards to the probabilities of any particular arrangements of degrees of freedom inside a closed system. A closed system is one which cannot exchange energy, volume, or particles with the environment. As such, there is quite literally no way for us to learn anything at all about how particles are arranged, so we must assume all arrangments that satisfy the given energy, volume and number of particles are equiprobable.

One link between statistical mechanics and classical thermodynamics is given by a definition of entropy:

|

(14) |

Note two important properties of  . First, it is extensive: if we consider a compound system made of subsystems

. First, it is extensive: if we consider a compound system made of subsystems  and

and  with

with  and

and  as the respective number of states, the total number of states is

as the respective number of states, the total number of states is

, and therefore

, and therefore

. Second, it is consistent with the second law of thermodynamics: putting any constraint on the system lowers its entropy because the constraint lowers the number of accessible states.

. Second, it is consistent with the second law of thermodynamics: putting any constraint on the system lowers its entropy because the constraint lowers the number of accessible states.

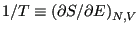

Temperature is defined using entropy:

, or

, or

|

(15) |

Now we will consider constraining our system not with constant  , but with constant

, but with constant  . The set of all possible states satisfying constraints of

. The set of all possible states satisfying constraints of  ,

,  , and

, and  is called the canonical ensemble. We now ask, what is the probability of any microstate in this ensemble? Consider a closed system divided into a small subsystem

is called the canonical ensemble. We now ask, what is the probability of any microstate in this ensemble? Consider a closed system divided into a small subsystem  surrounded by a large “bath”

surrounded by a large “bath”  . We imagine that these two subsystems exchange only thermal energy, but no particles, and their volumes remain fixed. We seek to compute the probability of finding the total system in a state such

that subsystem

. We imagine that these two subsystems exchange only thermal energy, but no particles, and their volumes remain fixed. We seek to compute the probability of finding the total system in a state such

that subsystem  has energy

has energy  . The entire system is microcanonical, so the total energy,

. The entire system is microcanonical, so the total energy,  is constant, as is the total number of states available to the system,

is constant, as is the total number of states available to the system,  (we omit the

(we omit the  and

and  for simplicity).

for simplicity).

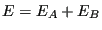

When  has energy

has energy  , the total system energy is

, the total system energy is

, where

, where  is the energy of the bath. By constraining system

is the energy of the bath. By constraining system  's energy, we have reduced the number of states available to the whole system to

's energy, we have reduced the number of states available to the whole system to

. So, using the fundamental postulate, the probability of observing the closed system in a state in which subsystem

. So, using the fundamental postulate, the probability of observing the closed system in a state in which subsystem  has energy

has energy  is

is

![$\displaystyle P_A = \frac{\left[\begin{array}{l} \mbox{Number of states for whi...

...} \end{array}\right]} = \frac{\Omega\left(E - E_A\right)}{\Omega\left(E\right)}$](img131.png) |

(16) |

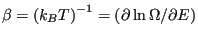

We can expand

in a Taylor series around

in a Taylor series around  :

:

where the partial derivative implies we are holding  and

and  fixed. We can truncate the Taylor expansion at the first-order term, because higher order terms become less and less important as the size of subsystem

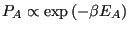

fixed. We can truncate the Taylor expansion at the first-order term, because higher order terms become less and less important as the size of subsystem  becomes larger and larger. What results is the Boltzmann distribution law for energies of a system at constant temperature:

becomes larger and larger. What results is the Boltzmann distribution law for energies of a system at constant temperature:

|

(19) |

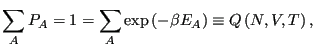

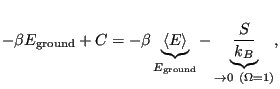

The normalization condition requires that for all energies of subsystem  ,

,  ,

,

|

(20) |

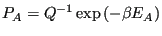

which defines the canonical partition function,  . Therefore,

. Therefore,

|

(21) |

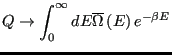

Because some energies can correspond to more than one microstate, we should distinguish between “states” and “energy levels.” We can express the canonical partition function as

|

(22) |

where, as we have seen,

is the number of microstates with energy

is the number of microstates with energy  . Moving to the continuum limit, and assuming a reference energy of

. Moving to the continuum limit, and assuming a reference energy of

,

,

|

(23) |

where

is the density of states. What is this equation telling us? It is telling us that

is the density of states. What is this equation telling us? It is telling us that  is the Laplace transform of

is the Laplace transform of

. We know that transform pairs are unique, and hence, both

. We know that transform pairs are unique, and hence, both  and

and

contain the same information.

contain the same information.

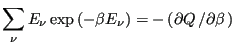

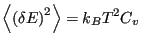

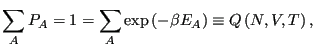

We recognize that for a system described by a canonical ensemble, the

energy is a fluctuating quantity. And we now have the probability of

observing a state with a given energy, so we can use

Eq. 1 to compute the average energy,

. Consider

. Consider

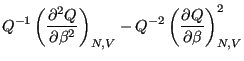

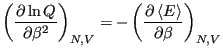

Notice that

|

(26) |

Recalling that

, we see that

, we see that

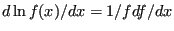

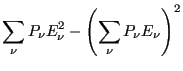

Now, let us consider the average magnitude of the fluctuations in energy

in the canonical ensemble.

Now, noting that the definition of heat capacity at constant volume,  ,

is

,

is

|

(34) |

we see that

|

(35) |

This is an interesting statement. It relates the magnitude of

spontaneous fluctuations in the total energy of a system to that

system's capacity to store or release energy due to changing its

temperature.

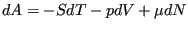

The fact (Eq. 28) that the average energy in the

canonical ensemble is related to a derivative of the log of the

partition function implies that  is an important thermodynamic

quantity. So, let's go back to our undergraduate thermodynamics

course(s) and recall the following statement of the 1st and 2nd Law:

is an important thermodynamic

quantity. So, let's go back to our undergraduate thermodynamics

course(s) and recall the following statement of the 1st and 2nd Law:

|

(36) |

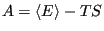

where  is the Helmholtz free energy, defined in terms of

internal energy and entropy as

is the Helmholtz free energy, defined in terms of

internal energy and entropy as

|

(37) |

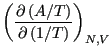

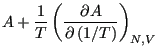

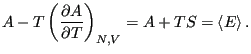

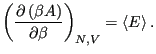

Now, consider the following derivative of  :

:

Therefore,

|

(40) |

Considering Eq. 28, we see that

|

(41) |

which does indeed suggest an important link between  and the

important thermodynamic quantity, the Helmholtz free energy. But what

is the constant

and the

important thermodynamic quantity, the Helmholtz free energy. But what

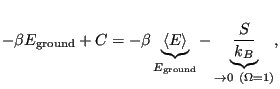

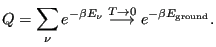

is the constant  ? To evaluate it, consider the “boundary condition”

as

? To evaluate it, consider the “boundary condition”

as

:

:

|

(42) |

Here, we have assumed that the degeneracy of the ground state,

is 1. This tells us that

is 1. This tells us that

|

(43) |

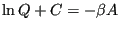

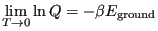

Using this fact, and combining Eqs. 37 and 41, as

, we see that

, we see that

|

(44) |

Hence,  = 0. So,

= 0. So,

|

(45) |

The quantity

is the Helmholtz free energy,

is the Helmholtz free energy,  .

.

cfa22@drexel.edu

![]() as the number of states available to a system under the constraints of constant number of particles,

as the number of states available to a system under the constraints of constant number of particles, ![]() , volume,

, volume, ![]() , and energy

, and energy ![]() . The fundamental postulate of statistical mechanics, also called the “rational basis”, is the following:

. The fundamental postulate of statistical mechanics, also called the “rational basis”, is the following:

,

, and

are equally probable.

![]() , or

, or

![]() has energy

has energy ![]() , the total system energy is

, the total system energy is

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the energy of the bath. By constraining system

is the energy of the bath. By constraining system ![]() 's energy, we have reduced the number of states available to the whole system to

's energy, we have reduced the number of states available to the whole system to

![]() . So, using the fundamental postulate, the probability of observing the closed system in a state in which subsystem

. So, using the fundamental postulate, the probability of observing the closed system in a state in which subsystem ![]() has energy

has energy ![]() is

is

![$\displaystyle P_A = \frac{\left[\begin{array}{l} \mbox{Number of states for whi...

...} \end{array}\right]} = \frac{\Omega\left(E - E_A\right)}{\Omega\left(E\right)}$](img131.png)

![$\displaystyle \exp\left[\ln\Omega\left(E\right) - E_A\frac{\partial\ln\Omega}{\partial E} + \cdots\right],$](img137.png)

![]() . Consider

. Consider

![$\displaystyle \left[\sum_\nu E_\nu \exp\left(-\beta E_\nu\right)\right] \left/ \left[\sum_\nu \exp\left(-\beta E_\nu\right)\right] \right.$](img150.png)

![]() is an important thermodynamic

quantity. So, let's go back to our undergraduate thermodynamics

course(s) and recall the following statement of the 1st and 2nd Law:

is an important thermodynamic

quantity. So, let's go back to our undergraduate thermodynamics

course(s) and recall the following statement of the 1st and 2nd Law: